Tidal Heating in White Dwarf Binaries

The Tides That Heat Up: New Insights into Inflated White Dwarfs in Binary Systems

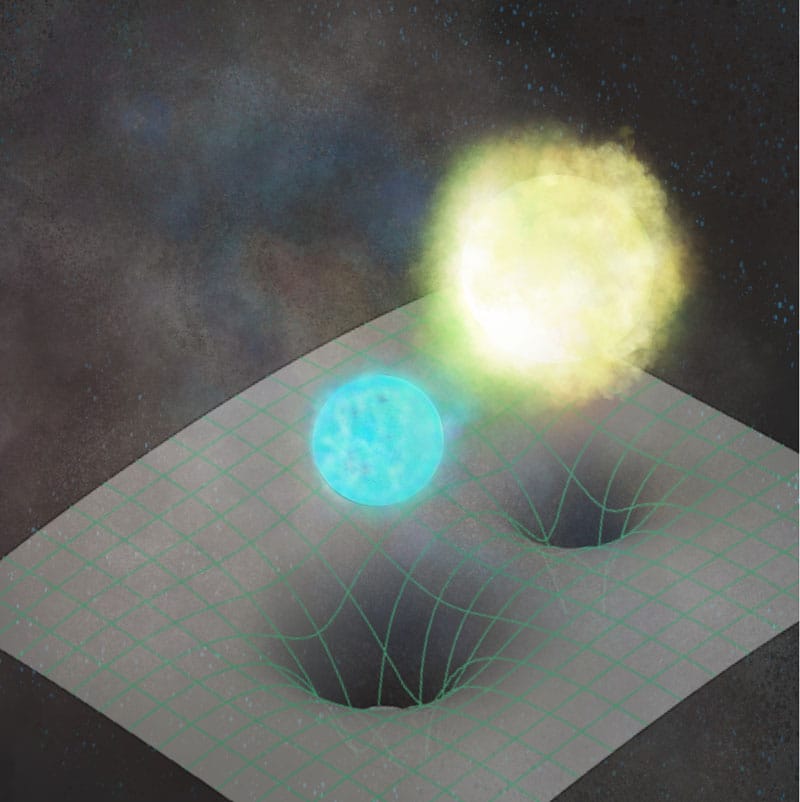

In the dance of stellar remnants, where white dwarfs orbit each other in tight, rapid spirals, a subtle force is reshaping our understanding of cosmic evolution. New research from astronomers at Kyoto University reveals that tidal heating—much like the gravitational tug that warms Earth's oceans—plays a starring role in puffing up these dense stars, making them hotter and larger than expected. This could extend the timelines for when binary white dwarfs begin sharing material, influencing everything from supernova explosions to the whispers of gravitational waves detectable by future observatories.

The Puzzle of the "Puffed-Up" White Dwarfs

White dwarfs, the cooling embers left behind by stars like our Sun, should shrink and chill over billions of years, supported by quantum degeneracy pressure rather than nuclear fusion. Yet, observations from surveys like the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the Zwicky Transient Facility paint a different picture for those in short-period binaries—systems where orbits zip around in under an hour. These "detached double white dwarf binaries" feature components that are surprisingly inflated, with radii up to twice as large as predicted for fully degenerate stars, and surface temperatures soaring above 10,000 Kelvin—hot enough to rival the heart of a blast furnace.

"This mismatch has puzzled astronomers for years," explains Lucy O. McNeill, lead author of the study published in The Astrophysical Journal. "We see these extremely low-mass white dwarfs, often made of helium, appearing younger and more vigorous than their age suggests." The culprits? Not residual heat from formation, but ongoing tidal interactions. As the pair spirals inward, driven primarily by gravitational wave emission, the gravitational pull between them deforms the less massive (but larger) white dwarf, generating internal friction. This friction dissipates energy as heat, much like rubbing your hands together on a cold day—except on a stellar scale, where it can swell the star's radius by thermal expansion.

A Temperature-Dependent Approach

To untangle this, McNeill and collaborator Ryosuke Hirai turned to established astrophysical tools, blending them in a fresh way. They started with numerical simulations of helium white dwarf cooling from J. A. Panei and colleagues (2000), crafting a mass-radius relation that flexes with surface temperature: hotter stars puff up like a balloon in the sun. For a 0.2 solar-mass white dwarf at 20,000 K, this means a radius about 0.03 solar radii—nearly double the "cold" limit of 0.015.

Next, they extended the equilibrium tide model pioneered by P. Hut in 1981, originally used to explain the orbits of "hot Jupiters" around their stars. This framework treats the white dwarf's tidal bulge as a dynamic response: the companion's gravity raises a quadrupolar distortion, and internal friction (viscosity in the star's layers) lags it slightly, converting orbital energy into heat. Unlike more complex dynamical tide models that rely on resonant stellar oscillations—which demand detailed internal structures—their approach is broadly applicable, sidestepping assumptions about specific wave modes.

"Tidal heating has had some success in explaining temperatures of hot Jupiters and their orbital properties with their host stars," McNeill notes. "So we wondered: to what extent can tidal heating explain the temperatures of white dwarfs in short-period binaries?" By coupling this to orbital decay equations from P. C. Peters (1964), they simulated evolution from present-day observations to the brink of mass transfer, when the donor white dwarf's Roche lobe—the gravitational boundary beyond which material spills over—fills up.

Hotter Stars, Longer Orbits, and Cosmic Ripples

Applying their model to nine eclipsing detached double white dwarf binaries from the Zwicky Transient Facility and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (detailed in the study's Table 1), the team found encouraging consistency with data. For the hottest primaries today, tidal heating predicts surface temperature boosts of up to 40% before Roche lobe overflow—translating to radius expansions that further delay contact. Crucially, even ancient white dwarfs, cooled to near-degeneracy over 10 billion years, reignite via tides in their final million years, arriving at mass transfer hot and bloated.

This shifts the onset of interaction: instead of the roughly 5-minute orbital periods assumed for cold, degenerate donors, their calculations point to roughly 17 minutes (2 millihertz gravitational-wave frequency)—over three times longer. "We expected tidal heating would increase the temperatures of these white dwarfs, but we were surprised to see how much the orbital period reduces for the oldest white dwarfs when their Roche lobes come into contact," McNeill reflects.

For the Galactic population, this implies a steady stream of interactions at lower frequencies, where space-based detectors like LISA (set for launch in the 2030s) will listen. Binaries like Zwicky Transient Facility J1539+5027, already at 415 seconds per orbit, could serve as test cases, with tidal contributions to decay matching observed roughly 10% deviations from pure gravitational waves.

From Transients to Gravitational Waves

These findings ripple outward. Mass-transferring detached double white dwarf binaries seed diverse exotica: hydrogen-deficient AM Canum Venaticorum binaries, R Coronae Borealis stars with their enigmatic dimming, and even ".Ia" supernovae—faint explosions from helium detonations. By favoring stable transfers at wider separations, tidal inflation may tilt rates toward certain outcomes, like calcium-rich gap transients over mergers.

The model also opens doors for carbon-oxygen white dwarfs, potential double-degenerate progenitors of brighter Type Ia supernovae—the "standard candles" calibrating cosmic distances. "The team plans to apply the framework to binary systems with carbon-oxygen white dwarfs to learn about Type Ia explosion progenitors," the Kyoto University release highlights, "focusing on whether realistic temperatures favor the double-degenerate merger scenario."

Still, caveats remain: the equilibrium model assumes circular orbits and simplified friction, and real stars may harbor convective quirks amplifying heat. Future surveys, like those from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, could spot more eclipsing pairs to test predictions, while LISA's millihertz band promises direct verification.

This work, grounded in observation and theory, subtly reframes white dwarf binaries not as passive relics, but as dynamically heated actors in the universe's grand theater—offering promising pathways to decode their explosive finales.