Deuteron Formation

Decades-old mystery in particle physics solved

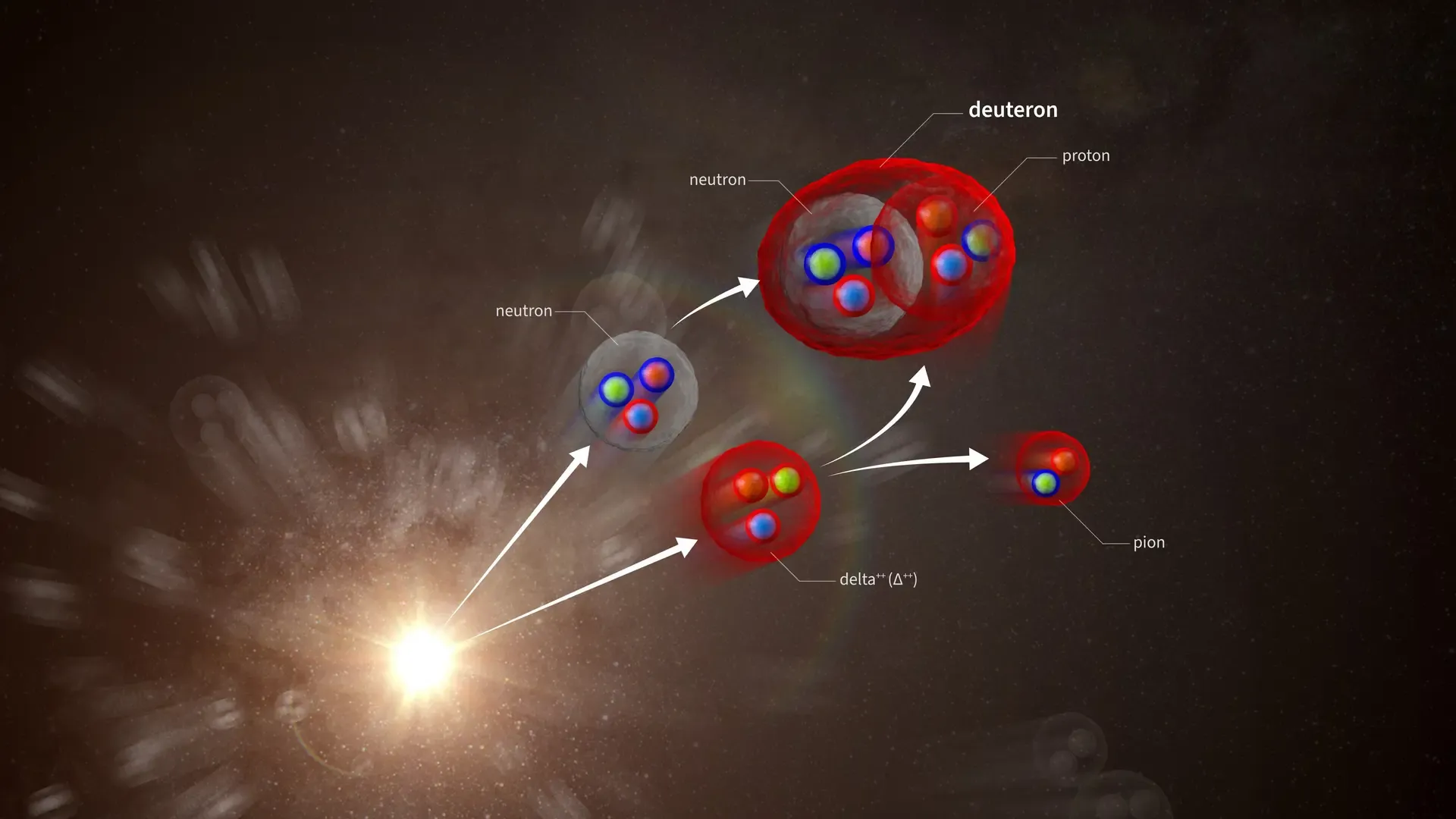

New research from the ALICE Collaboration at CERN, led by scientists from the Technical University of Munich, has resolved a decades-old puzzle in particle physics. By analyzing momentum correlations in proton-proton collisions, the team observed that approximately 90% of deuterons and antideuterons—light nuclei composed of a proton and a neutron—emerge from the decay of short-lived resonances, rather than forming directly in the scorching initial phase of the collision. These findings, published in Nature, offer a clearer picture of nucleosynthesis under extreme conditions.

The Puzzle of Light Nuclei

High-energy particle collisions, such as those at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), create environments hotter than 100,000 times the Sun's core. In these settings, temperatures exceed 100 MeV, far outstripping the few MeV binding energies that hold light nuclei like deuterons together. Yet, deuterons and their antimatter counterparts have been repeatedly detected in such experiments, raising questions about their formation and survival.

This phenomenon extends beyond collider physics. Understanding how these nuclei form is crucial for modeling cosmic ray compositions and potential signals from dark matter decays. Previous models, including statistical hadronization and coalescence approaches, could describe yields but lacked direct evidence of the underlying mechanisms. The ALICE team addressed this gap by examining pion-deuteron correlations, providing model-independent insights into whether deuterons arise thermally or through secondary binding processes.

Probing Formation with Femtoscopy

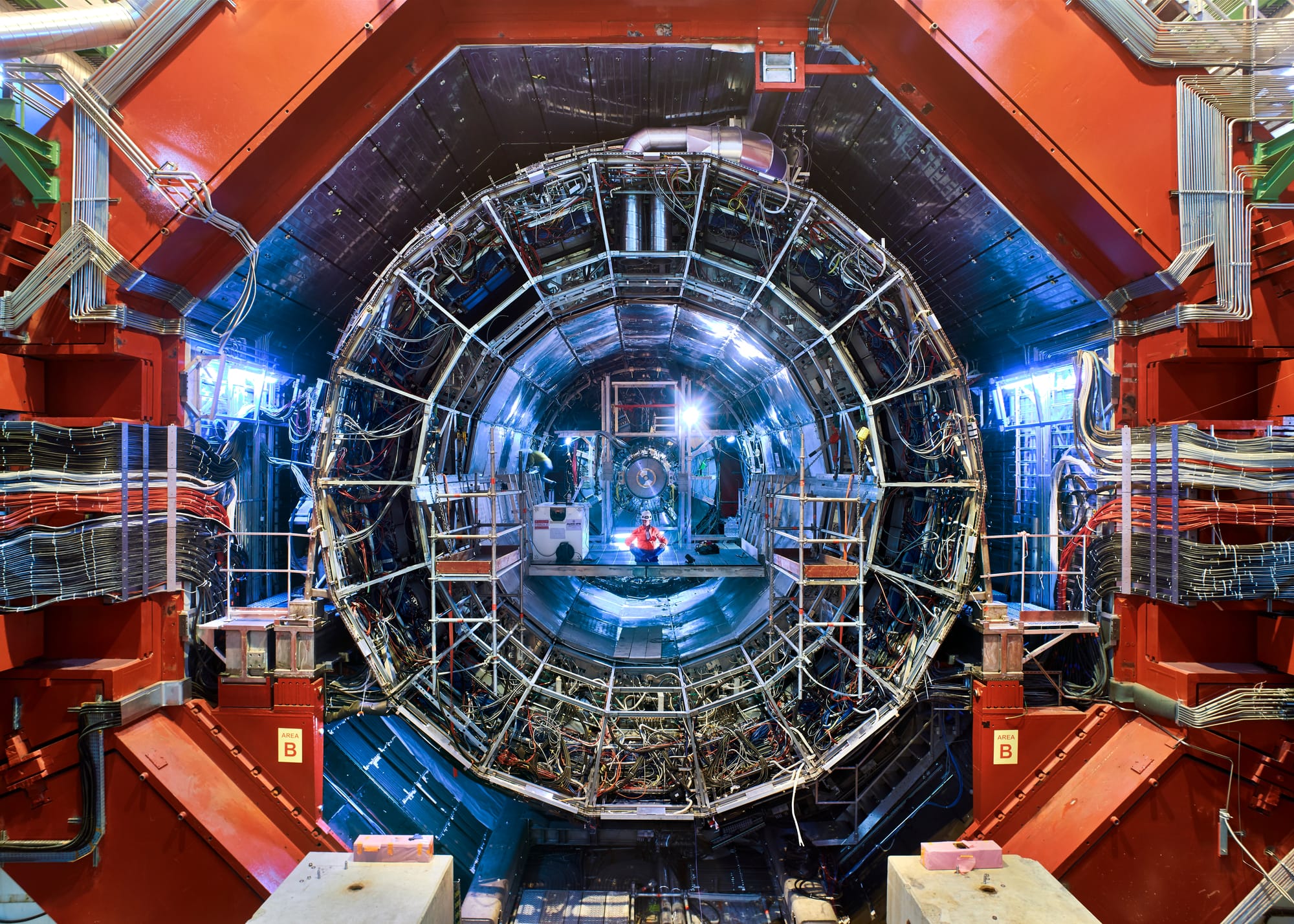

The study utilized femtoscopy, a technique that measures momentum correlations between particles to probe their interactions at femtometer scales—about the size of a nucleus. Researchers analyzed data from proton-proton collisions at a center-of-mass energy of 13 TeV, collected during the LHC's Run 2 from 2016 to 2018. This dataset included over 500 million high-multiplicity events, selected for their dense particle production.

Charged pions and (anti)deuterons were identified using the ALICE detector's Time Projection Chamber and Time-of-Flight systems, achieving purities of 99% for pions and 100% for deuterons. Correlation functions were constructed by comparing relative momenta of pairs from the same event against a mixed-event baseline, normalized to unity at large momenta.

To interpret these functions, the team employed the Correlation Analysis Tool using the Schrödinger equation (CATS) framework. They modeled the emission source as a Gaussian with an effective radius of about 1.5 fm, accounting for contributions from short-lived resonances. Simulations with tools like ThermalFIST, SMASH, and EPOS 3 tested scenarios: direct thermal production, elastic/inelastic scattering, and resonance-assisted fusion. The Δ(1232) resonance, decaying into pion-nucleon pairs after roughly 1.5 fm/c, played a central role in these models.

Resonance-Decay Dominates

Results indicated a prominent peak in the pion-deuteron correlation function at relative momenta around 240 MeV/c, aligning with the Δ resonance mass. This signature points to deuterons forming via nucleon binding after resonance decay, inheriting correlations from the parent resonance.

Fits to the data showed that 60.6 ± 4.1% of deuterons stem from Δ resonances alone. Scaling to include all resonances—Δ contributing 77.3 ± 1.2% of cases—yields an estimate of 88.9 ± 6.3% for resonance-assisted formation. The remaining fraction may arise from direct production or other processes.

These observations confirm that deuterons do not form in the hot initial quark-gluon plasma but later, when conditions cool to spectral temperatures around 20 MeV. As Prof. Laura Fabbietti from TUM notes, "Our result is an important step toward a better understanding of the 'strong interaction'—that fundamental force that binds protons and neutrons together in the atomic nucleus. The measurements clearly show: light nuclei do not form in the hot initial stage of the collision, but later, when the conditions have become somewhat cooler and calmer."

Broader Implications for Astrophysics

The findings have encouraging implications for fields beyond particle physics. Improved models of nucleus formation can refine predictions for cosmic ray spectra, aiding in identifying acceleration mechanisms in the Universe. They also enhance indirect dark matter searches by better quantifying antinuclei production from cosmic ray interactions or decays.

Dr. Maximilian Mahlein, a researcher at Fabbietti's Chair for Dense and Strange Hadronic Matter at TUM, explains: "Our discovery is significant not only for fundamental nuclear physics research. Light atomic nuclei also form in the cosmos—for example in interactions of cosmic rays. They could even provide clues about the still-mysterious dark matter. With our new findings, models of how these particles are formed can be improved and cosmic data interpreted more reliably."