2.7 Million Year Old Tools

New research shows a 300,000-year presence of toolmaking along an ancient river in the Turkana Basin

New research from George Washington University suggests that early hominins sustained Oldowan tool-making practices for approximately 300,000 years, even as their environment in the Turkana Basin transitioned from lush floodplains to arid grasslands. This discovery highlights the role of technology in navigating ecological challenges, offering insights into the foundations of human resilience.

Uncovering Namorotukunan: A Rare Glimpse into Pliocene Toolmaking

In the northeastern Turkana Basin, Kenya, archaeologists have excavated a site called Namorotukunan, revealing the earliest known Oldowan tools in the Koobi Fora Formation. Dated between 2.75 and 2.44 million years ago, these artifacts span three distinct horizons within a fluvial paleoriver system. Unlike most early Oldowan sites, which capture snapshots of behavior at single points in time, Namorotukunan provides evidence of sustained tool production over hundreds of thousands of years.

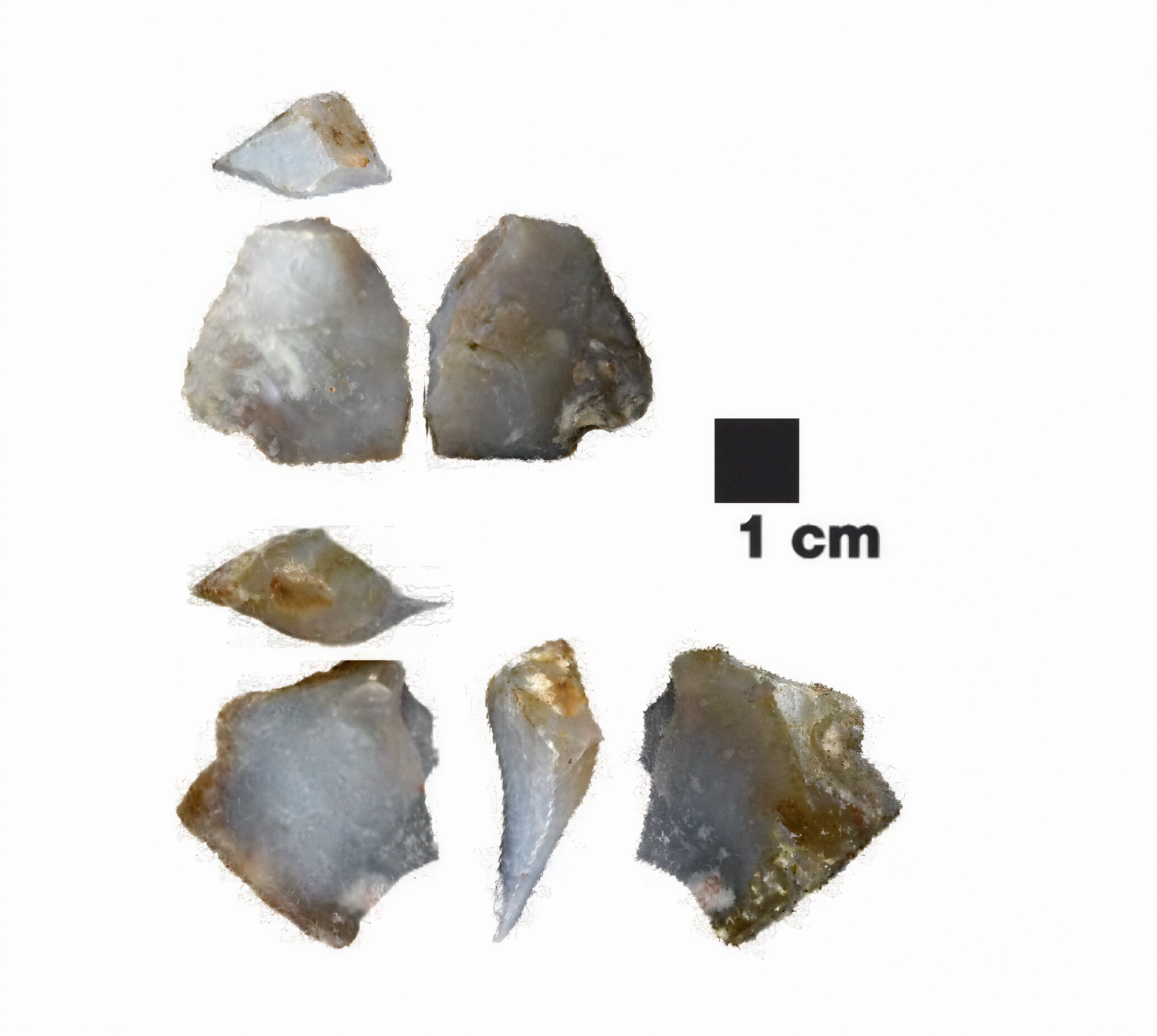

The site, located in Paleontological Collection Area 40, yielded over 1,290 artifacts, including sharp-edged flakes and simple cores, alongside fossilized faunal remains. Some bones bear butchery marks, indicating that these tools were used to access high-quality resources like meat and marrow from large mammals. "This site reveals an extraordinary story of behavioral flexibility and cultural continuity," said lead author David R. Braun, a professor of anthropology at the George Washington University. "What we’re seeing isn’t a one-off innovation—it’s a long-standing technological tradition."

Methodology: Reconstructing Ancient Environments and Behaviors

Researchers employed a multidisciplinary approach to date and contextualize the finds. Geological mapping identified sedimentary packages, including red paleosols, gravels, and lake clays, correlated with the Tulu Bor Tuff (dated to 3.44 million years ago) and paleomagnetic polarity zones. This framework placed the artifact horizons within the late Pliocene to early Pleistocene, aligning with the Gauss-Matuyama reversal at 2.61 million years ago.

Paleoenvironmental proxies, such as pedogenic carbonates, plant wax biomarkers, phytoliths, and microcharcoals, reconstructed habitat changes. For instance, shifts in carbon isotope ratios (δ13C) indicated an increase in C4 vegetation—grasses typical of open savannas—around 2.7 million years ago, coinciding with higher wildfire frequency and reduced water availability.

Artifact analysis focused on technological attributes, like flake scars and raw material selectivity. Hominins consistently preferred chalcedony, a fine-grained rock that fractures predictably, over locally abundant alternatives. Comparisons with other Oldowan assemblages, such as those from Ledi-Geraru and Nyayanga, confirmed similarities in core rotation and fracture mechanics.

Key Findings: Technological Stability in a Changing World

Results indicated remarkable continuity in tool-making behaviors across the 300,000-year span. Artifacts from all horizons showed high proportions of sharp flakes (79-94%), with cores exhibiting few scars and minimal rotation—hallmarks of early Oldowan technology. Despite environmental shifts toward aridity, hominins maintained selective practices, adapting tools for extractive foraging without evidence of long-distance transport.

The paleoenvironmental data revealed a transition from wetter, palm-dominated habitats to drier grasslands with frequent fires. Yet, tool production persisted, suggesting that Oldowan technology buffered against these changes. Butchery marks on bones from the 2.58-million-year-old horizon further link tools to dietary expansion, potentially aiding survival in variable ecosystems.

"Namorotukunan offers a rare geological lens into a changing world long gone—where shifting rivers, wildfires, and aridification reshaped the landscape over and over," noted co-author Dan V. Palcu. "Yet despite these environmental challenges, early human ancestors were able to survive using their tool-making tradition, perhaps revealing the roots of one of humankind’s oldest habits: using technology to steady ourselves against change."

Implications for Understanding Human Evolution

This study underscores the interplay between environmental variability and technological innovation during a pivotal period in hominin evolution. By thriving amid Pliocene aridification, early toolmakers may have laid the groundwork for broader adaptations, including expanded diets and habitat exploitation. The findings align with broader patterns in eastern Africa, where open savannas emerged around 2.8 million years ago, potentially driving shifts toward tool-mediated resources like underground storage organs and animal tissues.

Encouraging results point to cultural transmission across generations, as consistent practices suggest knowledge passed down despite ecological pressures. However, the researchers emphasize that these insights are provisional, derived from a single locale, and call for further excavations to confirm regional patterns.

As global climates continue to change, this ancient example offers subtle optimism: human ingenuity, rooted in simple technologies, has long enabled adaptation. Future research could explore similar sites to deepen our understanding of these evolutionary dynamics.